Analysis

3/3/21

7 min min read

Study: What's the Shelf Life of an NFL Defensive Coordinator?

After looking at the average tenure of an NFL offensive coordinator last week (read it here), this week we are going to evaluate their defensive counterparts. As we’ll see, defensive coordinators show more stability, with only 234 new hires at DC since 2000, or roughly 11 each year. Only one season since the turn of the century has seen over 15 new DCs. That was in 2009, when there were 21 new hires -- prompting the only dip in scoring over a nine-year span (2005-2013). As we’ll see, the role is still highly demanding, but in a different way than for offensive coordinators.

The same note from the study on OCs applies here: a defensive coordinator hire is defined as a designated DC starting the year with a new team. If implementing your offense midseason is considered difficult, implementing a different defensive scheme without an offseason to prepare is nearly impossible. Additionally, the study only considers DCs hired since 2000 – unfortunately disqualifying some excellent tenures that stretched into the 21st century, like Monte Kiffin (TB), Jim Johnson (PHI) and Marvin Lewis (BAL).

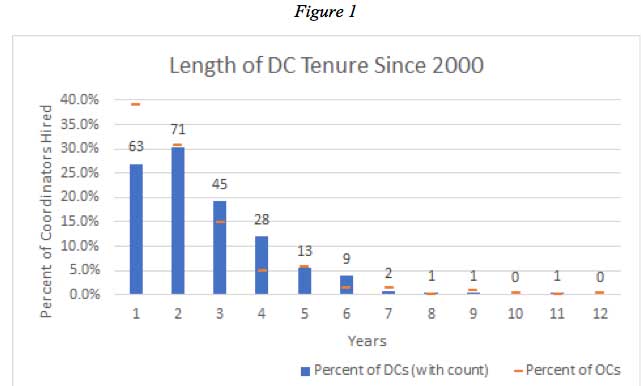

In the figure above, the blue bars represent the percentage of all DCs who had a tenure of that length. For example, 63 DCs (26.9%) lasted exactly one year, while 28 lasted exactly four seasons (11.9%). The orange lines above each column are the corresponding figures for the offensive coordinators, mostly valuable as comparison. The average tenure for a DC is 2.62 years, significantly above the offensive coordinators’ 2.29 average tenure. Notably, only 12.5% of DCs make it to a fifth season, while a similar percentage of offensive coordinators make it to a fourth season.

The first, and largest, takeaway comes in the shape of the graph. Nearly three-quarters of DCs make it to year two, with that second year most frequently being the stopping point. This is a stark contrast to the offensive coordinator graph where we saw a high point of nearly 40% of coordinators only getting one season before a steady decrease each season.

Additionally, there’s much less contamination in this graph from coordinators hired to be head coaches. Of the 11 HCs in 2021 who have a defensive background, they spent an average of three seasons in a DC role immediately before their current position, and even that number is skewed by a few one-and-dones like Brandon Staley, Mike Tomlin, and Mike Vrabel. Even more, Brian Flores was not labeled as a DC prior to his hiring as Miami’s HC, and therefore counts as 0. More commonly of the current HC crop, it takes exactly six years as a DC to get the top gig, as it did with Sean McDermott, Vic Fangio and Mike Zimmer. In the spirit of completeness, the remaining active defensive HCs, and their years immediately prior as a DC, are Robert Saleh (4), Bill Belichick (3), and Ron Rivera (3). It’s clear that this impact on the average tenure of a DC is much more spread out, and less pronounced.

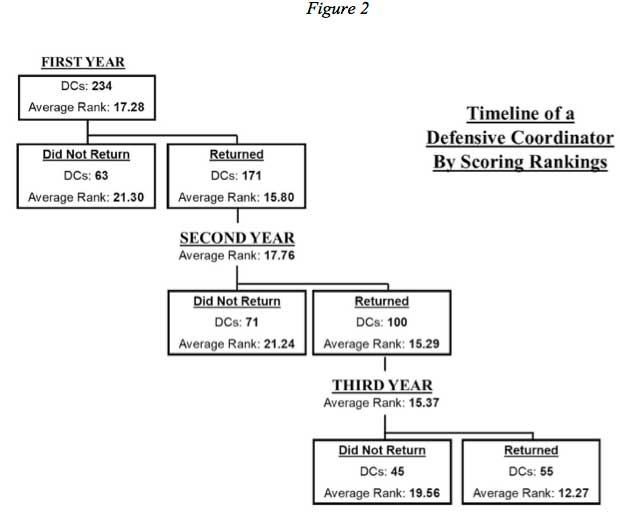

The most important role of any defensive coordinator is to prevent the other team from scoring. By looking at how DCs fare throughout their tenure in terms of scoring (allowed) rankings, it’s possible to get into the minds of those making the hiring decisions and start to understand how DCs are valued.

The first note of value is the overall average rankings. In both their first and second years, DCs average a bottom-half finish, allowing more points than the league average. When considering the early chart that describes how the vast majority of DCs make it to at least a second season, the lack of any improvement in the second year is unsurprising. However, it’s notable to look at the average rankings of those who did not return in each of those seasons: both roughly 21st. In a league of 32, a bottom-10 finish seems to be putting the jobs of DCs in serious jeopardy, although anything better than that is fairly safe.

By the third year of their role, we begin to see a split similar to the offensive coordinators, where only the top coordinators are being retained (average ranking of 12th), while those not at that level are not likely to return. As with the offensive guys, it’s fair to expect this split to continue and for the less-productive DCs to continue to be filtered out, leaving only the strongest DCs remaining. However, in a study-defining result, this is not at all the outcome. In their fourth year, defensive coordinators continue their barely-above-league-average finish with a 15.53 average scoring ranking, but the 27 coordinators that make it to their fifth year still don’t show an ability to consistently put together productive defenses, averaging the same 17th scoring ranking that is seen by first-year DCs. In fact, it’s not until year 6, in which only 14 defensive coordinators remain (and several were subsequently hired as HCs), that we truly find the guys who can consistently prevent the opposition from putting up points, averaging a 12.00 scoring ranking.

Why? With offensive coordinators, it only took until year 3 for a consistent top-third scoring ranking, indicating that the less-productive guys were filtered out. So why does it take until an astounding sixth year for the same result with defensive coordinators? By no means does this study have all the answers, but there’s a couple relevant factors we can point to.

First, it’s likely harder to lead a consistently-productive defense. As seen last week, nearly all of the longest-lasting offensive coordinators benefitted from standout QB play, whether from a Hall of Fame-level talent or a guy they managed to elevate. By hitting on that single draft pick or free agent signing, offenses can score for years. There’s no positional equivalent on the defense. The Minister of Defense himself, Reggie White, is rated as the top defensive player of all time by Approximate Value, and his teams on average ranked 10.3 in scoring defense. That’s good, but pales in comparison to the average offensive rankings of the top QBs. Players like Tom Brady (4.9), Drew Brees (6.5) and Peyton Manning (6.1) all led consistently higher-ranking offenses. Building a consistently productive defense requires building depth at most, if not all, positions and getting production each year.

Next, team management seems to be very consistent after the first year, with nearly exactly half of DCs returning in any given season. These decisions seem heavily reliant on the scoring rankings of that year, as the above chart showed the stark difference in scoring rankings between the DCs who returned and those who did not. For the most part, if a DC had a good year, he came back. If he didn’t, he didn’t. However, this methodology didn’t show any reliance in projecting future production, and the returning DCs didn’t show any ability to consistently beat the rest of the league until year 6. Management may be too focused on the most recent season and miss the larger picture, firing a DC who would have been productive in the future.

How can management improve in selecting capable DCs? While we can’t simply take the longest-lasting DCs, because they don’t show consistently improved production until year 6 (of which only 14 DCs hired this century, or 6%, reached), we can build a representative list that has the same effect by matching average scoring rankings to longevity. Specifically, there have been 31 defensive coordinator tenures in which they:

a) Were hired since 2000

b) Lasted at least three seasons

c) Averaged at least the 12th-best scoring defense

This gives us consistently productive DCs, but also a large enough sample size from which to draw conclusions. With 28 DCs total (Dean Pees, Rod Marinelli, and Romeo Crennel each made the list twice) spanning 20 distinct teams, this list doesn’t get caught with specific teams or players, but finds some of the most productive DC tenures. Among top teams at identifying and supporting these DCs are Pittsburgh, which has spent all 21 seasons this century with one of these DCs, as well as Baltimore (16 seasons), New England (14) and Cincinnati (10). As a caveat, the Patriots’ seven seasons without one of these tenures included six without a formal DC, presumably with HC Bill Belichick filling the role (but not counting as a DC in this study). On the opposite side, Cleveland joins 11 other teams without one of these tenures this century, but is notable in itself for only having a single DC (Todd Grantham) to make it to a third season (which was also his final season).

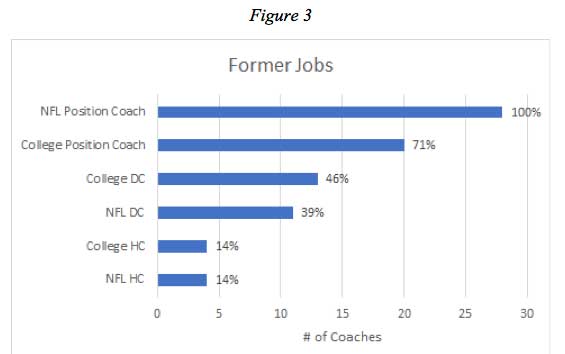

Looking at the former roles held by these DCs, the necessity of a background as a position coach is relentlessly apparent. While a few of the offensive coordinators could make the jump directly from a playing career to OC, this isn’t something that’s occurred with the defensive side of the ball. Additionally, there’s a far more standard track to becoming a DC. The vast majority of DCs were a college position coach first, making their way to the same role in the NFL (with some making stops in-between as a college DC), before getting promoted to NFL DC. Very few of this group were former HCs at either the NFL or college level, speaking to the difficulty of DCs getting those jobs.

Another notable finding is from evaluating the next job taken by our set of 31 DC tenures after their standout role was finished. While 4 remain active, the vast majority (97%) stay in the NFL in some capacity, with 11 taking another DC job, seven getting hired as an NFL HC and eight more working in some other capacity, usually as a defensive position coach or analyst. The only DC in this set to go immediately back to college was Brian VanGorder, leaving Atlanta to lead Auburn’s defense. Although we saw many offensive coordinators jumping between college and the NFL, this is far less pronounced on the defensive side, as guys who make it to an NFL DC job aren’t likely to go back to the collegiate ranks.

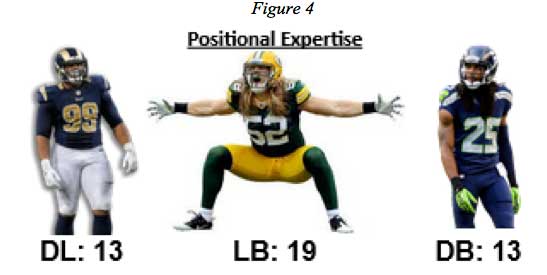

The final point to evaluate is the positional expertise of this group. While defensive coaching staffs have much more varied roles, requiring us to be more general in terms of positions, 68% of our DCs have prior experience coaching LBs. Similar to the offense’s TE position, coaching LBs requires extensive knowledge of techniques to stop the run, rush the passer and cover in space. When game-planning, many offensive coordinators will look to take advantage of the linebackers, so an ability to coach your linebackers to produce despite that focal point seems to give coaches a better understanding of what OCs will do and how to react.

Regardless, preventing points is still at a premium in the NFL, but it’s definitely a difficult task to accomplish. There are not many truly elite DCs, but finding one can transform your franchise.