Breakdowns

11/29/21

4 min read

Size vs Speed: How to Convert Short-Yardage

As we look at how best to convert short-yardage opportunities, let's take a look at two very different plays, both notable in Super Bowl history.

The first, John Riggins’ 43-yard touchdown run for Washington in the fourth quarter of Super Bowl XVII, taking the lead over the Don Shula-led Dolphins for the first time all day, enough to secure the franchise’s first championship in 40 years.

On fourth-and-one, out of 23 personnel, this carry (just one out of Riggins’ 38 on the day and 136 in the 1982 playoffs) came from the I-formation with not a single player detached from the formation. In short, it was just about as heavy of a package as possible. Washington made no secret of their design, having run this exact play three times already, but not even seven defenders on the line of scrimmage was enough to stop Riggins and The Hogs.

Twenty-seven years and a week later, Peyton Manning and the Colts faced a similar situation against the Saints in Super Bowl XLIV. Up a point early in the fourth quarter, Indianapolis faced a fourth-and-two just past midfield. In stark contrast with Riggins’ Romp, the Colts put three receivers on the field and spread them out.

With Manning under center and Joseph Addai as the singleback, the Saints were forced to put nine players within one yard of the line of scrimmage, but only six in the box. To the boundary side, hand-in-the-dirt Dallas Clark cleared out space with a slant route, leaving Reggie Wayne (who had lined up outside the numbers) ample room for his own slant to easily beat Tracy Porter and convert the down. Although Indianapolis didn’t manage to finish out the game, the concept was sound and easily gained the yardage required.

Which concept is actually more efficient in 2021 at converting short yardage?

Sean Payton and Joe Lombardi have used 6-plus OL in short-yardage situations more than anybody else this year, while Andy Reid and Kliff Kingsbury have been spreading the field in the same situations. Through the first 10 weeks of 2021, we identified 562 snaps where the offense used 6-plus offensive linemen, a key indicator that the team is going to use brute force.

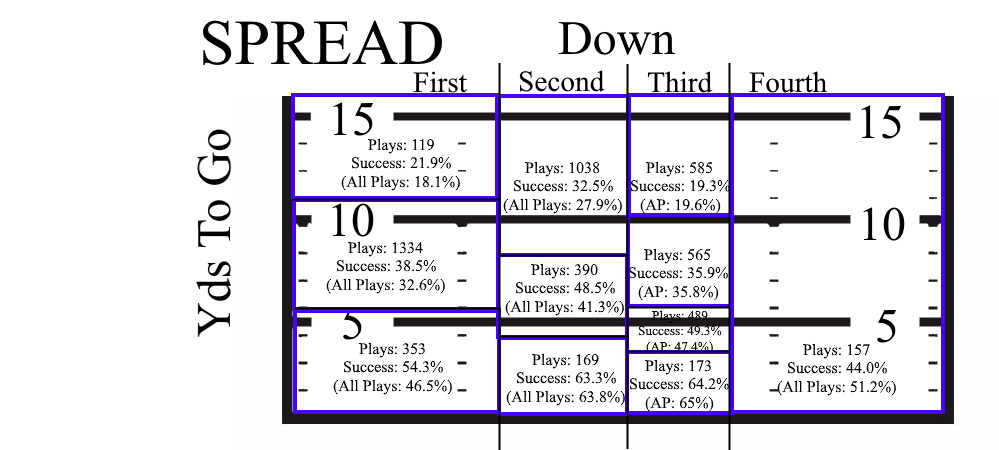

On the other hand, there’s no clear indicator for a spread-out formation, but we identified 5,054 snaps that included a light personnel, empty or gun backfield, and 3x1 or 2x1 formation that didn’t crowd around the tackle box. Using PFF’s success rate, which looks at whether a play gained half the required yardage on first or second down or whether it converted on third or fourth, we can evaluate which of these philosophies has been more effective in 2021.

Evaluating the spread philosophy first, we can compare it to the success rate of all 2021 NFL plays in that down and distance. The thing that immediately stands out is that this spread philosophy seems to be a lot better than average in early downs, but that doesn’t continue as we get into third and fourth down.

Although it is initially a bit of a head-scratcher, it makes more sense considering how frequently teams run the ball on early downs. From these spread packages, teams run at a 9.4% rate (12.82% on first-and-ten), while the typical run rate on first-and-ten is 48.23%. This would indicate that teams are actually running the ball too frequently on early downs and doesn’t much tell us whether spread packages are good in short distances.

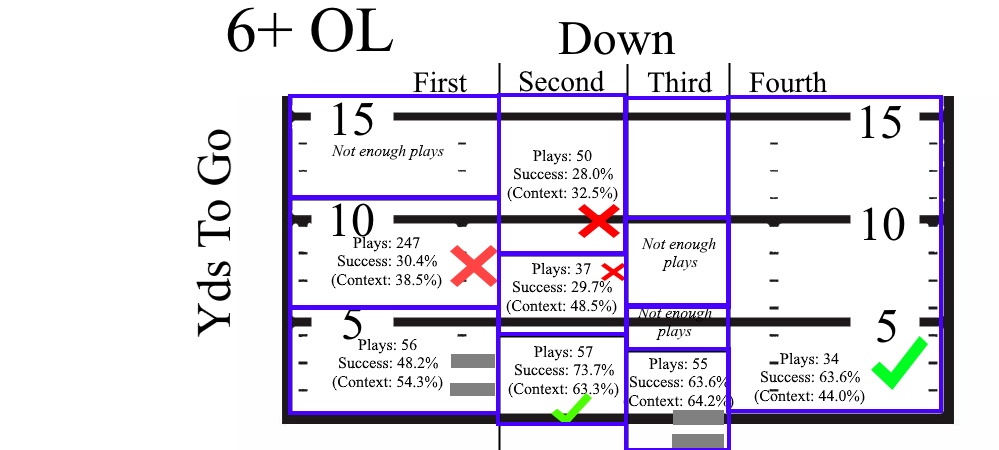

Let’s compare 6-plus OL packages to spread. In the below chart, “context” is the success rate for spread, a green check mark means that 6-plus OL is significantly better, a grey equal sign means that they are roughly equal, and a red X means that spread is significantly better.

This looks like what we would expect – spread is better in higher yards-to-go situations. However, the million-dollar question of which concept performs better in short yardage seems to be fairly clear – going heavy with 6-plus offensive linemen is still the more successful strategy, at least for now.

With linebackers getting smaller and an increase in the usage of nickel and dime packages, defenders are more easily able to cover space but can’t necessarily stop an oncoming offensive lineman. Spreading out the field is enormously beneficial to an offense, but if you need to pick up those final few yards, size still reigns supreme.