NFL Analysis

11/10/22

10 min read

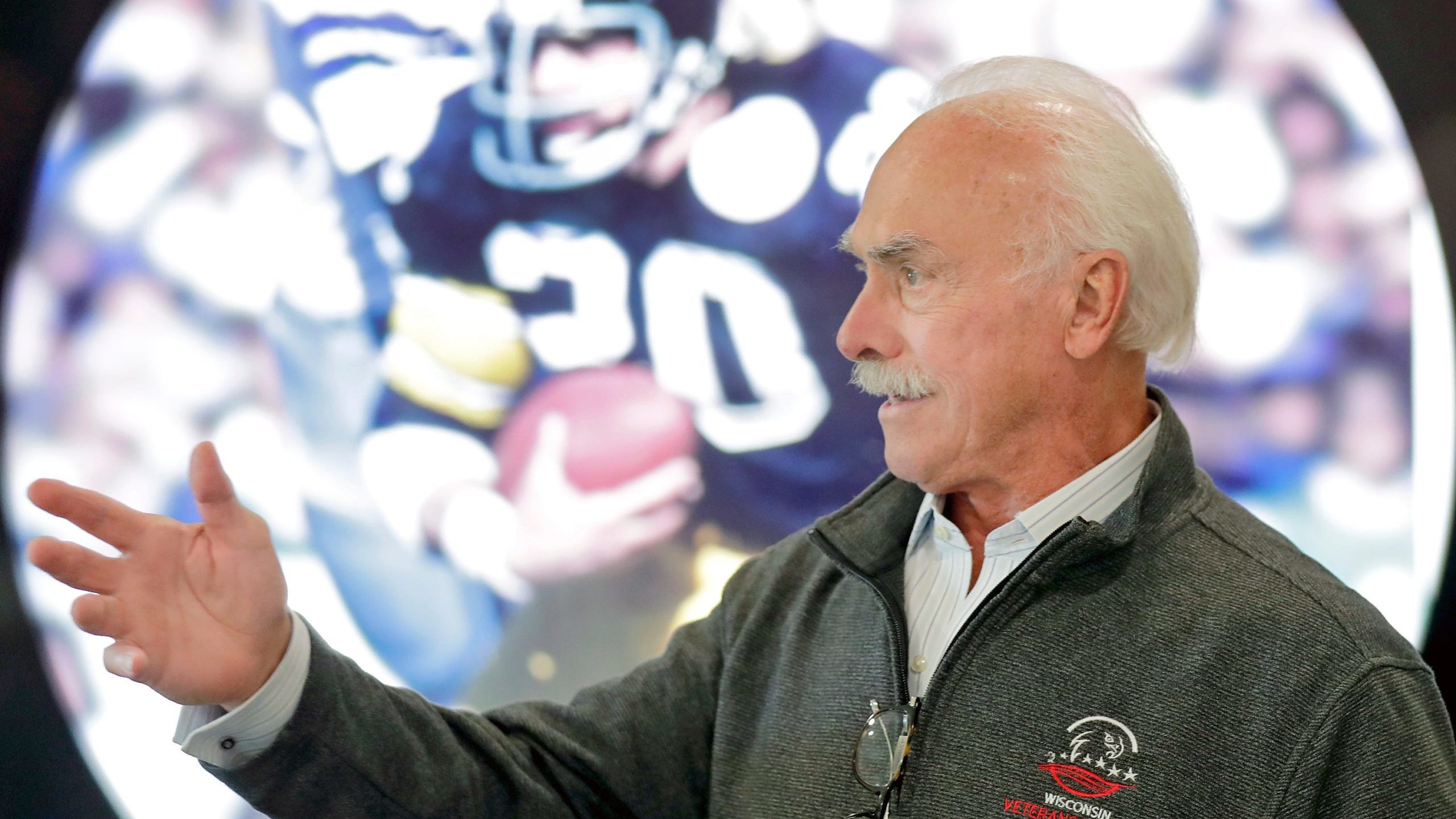

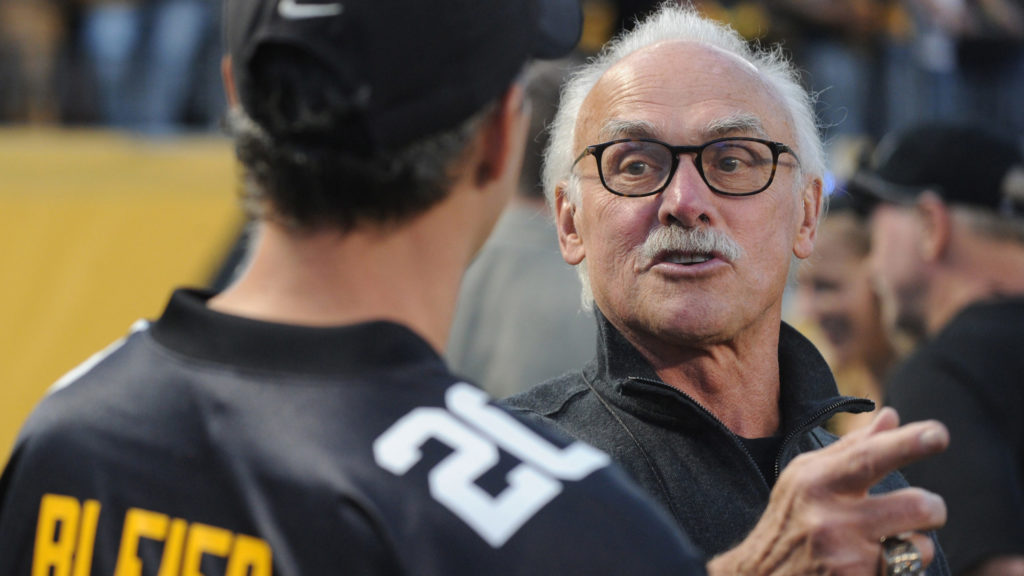

Steelers' Legend Rocky Bleier's Commitment to Veterans Hasn't Slowed

Shad Meshad is the president and founder of the National Veterans Foundation, which services more than a half-million veterans and their families. He has spent most of his adult life trying to help the broken soldiers who come home from war.

"The bottom line for me is no vet should be left behind,” said Meshad, who founded the NVF in 1985. "That's how it is in combat, but it's not that way here by our society and leadership.

"They're the missing in America. The invisible soldiers who come back and don't have a job or perspective of where to go. There's no transition. They spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to make you the best soldier you can be, but there's no money for when you come out and need to transition back.

"These are young men who have come back with war trauma. To navigate the VA (Veterans Administration) system, they're told when they're exiting the military to just go across the street and knock on the door, and they'll pick up where they left off. That's total bullshit."

Helping these veterans deal with the mental and physical damage done to them by war costs money for struggling non-profits like the NVF.

Enter Rocky Bleier.

Bleier's story is well known. A 16th-round draft pick by the Pittsburgh Steelers out of Notre Dame, he had his football career put on hold after his rookie year when he got drafted into the Army and shipped to Vietnam in 1969.

Three months after he got there, he was wounded by an enemy grenade that put more than a hundred pieces of shrapnel in his right foot and leg. He needed multiple surgeries to repair the damage, and the doctors told him he could live a normal life. But would he play football again? Yeah, no.

But Bleier proved them wrong. He made it back to the football field and played 10 seasons with the Steelers, winning four Super Bowls with the team.

As impressive as that was, though, what he's done in the 42 years since retiring from the NFL has been even more impressive. He has worked tirelessly for the last four-plus decades as a speaker, fundraiser, spokesman and activist for veterans and veterans organizations like the NVF.

"Rocky's been with me for more than 32 years, helping in any way he can," Meshad said. "He was a God shot that's never left. He's never forgotten the journey and just how hard it was. There are a lot of Vietnam vets who came back and have been successful. But they moved on. Rocky didn't do that. He has stepped up any time I've called him. He's just a special guy."

The 76-year-old Bleier, who owns a construction company in Pittsburgh, is working harder than ever to trumpet the cause of veterans.

"I have found myself in a position to at least make people aware of veteran's situations and needs and problems," Bleier said. "I'm proud to be able to help. There are people on the front lines like Shad that are working every day with veterans. They're the ones that are on the ground interacting. I just try to create awareness and raise money and things like that."

"The awareness of the American people is that if it doesn't touch them, the government should take care of their service people; the VA should take care of them," Bleier continued. "The VA was set up to do that, but only 22 percent of our veterans are using the VA. I'm not knocking the VA. It depends on where it's located and how it's set up. Some do a lot for veterans. Others are less able to do that. So, we have this mishmash. We have civilians who don't understand the military or whose responsibility it is to help them.

"And we have soldiers that come back and can't make transitions or have difficulties and don't want to have anything to do with the military, including the VA. They don't take advantage of what the VA has to offer. Then it falls back on the community to help that veteran to the best of their ability because he's their neighbor or relative."

The first thing you should know if you don't already is Bleier's story is nothing like Pat Tillman's. Bleier didn't wind up in the middle of a war in southeast Asia out of a sense of obligation to his country. He wound up there because he had no choice.

There was a military draft during the Vietnam war, but the few professional athletes who were drafted usually were given the option of joining the Reserves. Bleier fell through the cracks.

"I grew up in Wisconsin," he said. "I had seen pictures of Packers players in the reserves going for their two weeks during the summer. I was thinking I'll be fine."

But. he wasn't fine. In November, just as the Steelers were wrapping up a fifth straight losing season, Bleier received his induction notice.

"The letter said, ‘Greetings, we'd like to inform you that you've been inducted,"' he said. "I said, holy shit. I got the letter on Wednesday to be inducted on Thursday. It all happened in such a short period of time. I didn't have much time to dwell on it. I was sent to basic training, finished basic, then got my orders and ended up being sent to Vietnam that May."

In August, Bleier's company was involved in a firefight with the Vietcong. He took a bullet in his left thigh. A short time later, the enemy fired a grenade that landed near where Bleier and his commanding officer were positioned.

The grenade hit the commanding officer in the back, bounced off him and rolled between Bleier's legs. He was standing on top of it when it went off, blowing up on his right foot, knee and thigh.

A team of four soldiers eventually got Bleier to safety, using a poncho liner to carry him out. At one point, one of the soldiers lifted Bleier on his shoulder and carried him on his own. Their courageous efforts to extract him go a long way in explaining Bleier's lifelong commitment to his fellow veterans.

Bleier was flown to a hospital in Tokyo, where they performed surgery on his foot and leg. After the surgery, he asked his doctor about his chances of playing football again.

"He had a ward of soldiers he's taking care of, and all of a sudden, he's got a young soldier asking him about playing football," Bleier said. "He said you'll have a normal life. You'll be able to do all of the things that normal people do. But don't expect to go back to the gridiron.

You just won't have the strength or flexibility in that foot and leg to do the things necessary to play in the NFL again. His words just sucked the air out of the room for me."

Two days later, still feeling sorry for himself, Bleier received a postcard from an unexpected source that lifted his spirits.

"It said, ‘Rock, the team's not doing well. We need you,"' he recalled.

It was signed by Steelers owner Art Rooney.

The Steelers needed more than Bleier. A lot more. They finished 1-13 in 1969 under first-year coach Chuck Noll. But motivated by Rooney's message, Bleier vowed to do everything possible to get back on the field, regardless of what the doctors thought.

"It wasn't a matter of whether I could do it or not," he said. "I really wanted to come back and play. In my mind, I'm thinking, OK, you've been hurt before. You've been hurt playing in the backyard. You've been hurt playing in pickup games. You've been hurt in grade school and high school. There's a process to go through to get better, and you heal, and you're back out there playing again. That was my simple mindset.

"I wanted to eliminate all of the ifs. If I did that — if I got to a point where it didn't work out — as tough as that would've been to deal with, at least there would be no ifs. At least I did everything possible to come back."

Bleier's comeback was slow and arduous. But, the Steelers showed incredible patience. He spent the entire 1970 season on injured reserve.

He got bigger and stronger and spent most of the '71 season on the team's taxi (practice) squad. Finally, he made the team in '72, playing mostly on special teams.

"By '73, I was in the best shape of my life," he said. "I was up to 218 pounds. I was running the 40 in 4.55 (seconds). I was bench-pressing 465 pounds. I made the team again. But I was back playing special teams."

Frustrated over his limited role with the Steelers, Bleier decided after the '73 season to quit football.

That offseason, before he had a chance to tell anybody, Bleier happened to be in Chicago and got a call from Steelers linebacker and team captain Andy Russell. Russell was calling to invite Bleier to dinner. When Bleier declined, Russell asked why.

"I said, ‘Well, [because] I'm not going back,"' he said. "He gave me this speech. He said you can't quit. He said if you do that, you're already making a decision for the coaching staff. He asked me if I liked the coaching staff well enough to make a decision for them. He told me to come back and make them make a decision (on him). Back them into a corner and give them every reason to keep me. He said you don't cut yourself.

It made imminent sense. So, I came back in '74 because of that, and the rest is history. [Russell's words] changed the course of my life. The note from Mr. Rooney, and the conversation with Andy Russell — it's not that different from being involved with veterans and what the NVF does with their hotline. It's just that personal touch. Sometimes, it's like getting that postcard. Sometimes it's like getting that phone call. Sometimes it's only because somebody cares that may make the difference in pulling the trigger [on the gun] or not pulling the trigger."

Bleier returned to the Steelers in '74 and not only made the team but finally cracked the starting lineup, serving primarily as a blocking back for Franco Harris but also rushing for 373 yards as the Steelers won their first Super Bowl. A year later, Bleier rushed for 528 yards as the Steelers won the Super Bowl again.

In '76, Bleier and Harris became just the second running back tandem in history to each rush for 1,000 yards. Bleier would win two more Super Bowls with the Steelers before finally retiring after the 1980 season. He was inducted into the Steelers' Hall of Honor in 2018.

The Vietnam war was an unpopular war, and the soldiers who fought in it, many of whom, like Bleier, had no choice, often found themselves as the targets of much of the vitriol.

"The majority of Vietnam veterans came back at a time when the majority of the American people did not embrace the service, did not thank them," Bleier said. "They were looked down upon. There were times when you'd be on a plane, and they say, ‘We're landing. Please change into civilian clothes and get out of your army clothes.'

"So, the whole mindset during that period of time was people repressed their feelings [about fighting in the war]. They didn't talk about it. They went back to school or got married, got a job as they best possibly could, and went underground."