Analysis

2/15/23

7 min read

Sticking to Your Prototypes Vital in NFL Personnel Evaluation

This is the first of a two-part series examining the process of personnel evaluation. In this installment, we look at the importance of establishing a prototype for each position and staying true to it. For Part 2, we look at exact typing and numerical grading systems used in personnel evaluation.

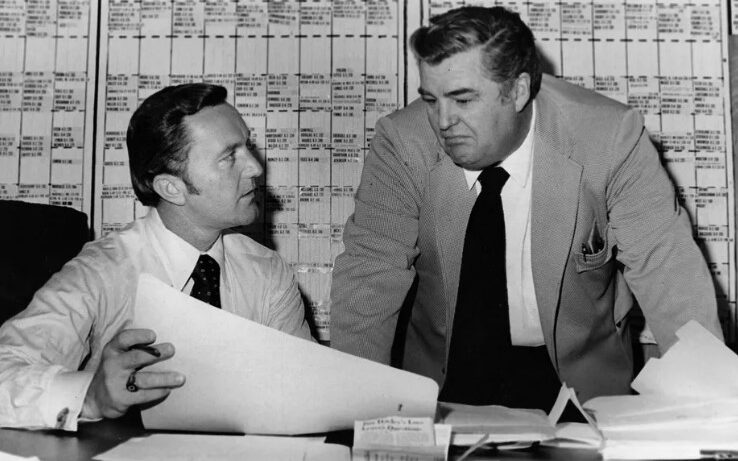

In my first year in professional football, as a linebackers coach with the New England Patriots, I was exposed to an astute personnel man named Francis "Bucko" Kilroy.

Bucko and his assistant, former Patriots head coach Mike Holovak, showed me a scouting system I took with me throughout my time in the NFL. As I went forward in coaching, personnel was an area that always interested me. For me, it wasn't a necessary evil. It was a labor of love, and I embraced it and grew with it, and learned from it. It took me multiple years to really understand that scouting system completely, the nuances of it, the specifics of it and the value of it, but I carried it with me my entire career.

This graph shows what the height, weight and speed prototypes were for our scouting system:

| Position | Height | Weight | 40-yard Time |

| QB | 6026 | 219.77 | 4.79 |

| FB | 6006 | 246.07 | N/A |

| RB | 5016 | 212.63 | 4.54 |

| SLWR | 5112 | 193.98 | 4.48 |

| OWR | 6010 | 201.96 | 4.47 |

| TE | 6045 | 248.27 | 4.70 |

| OC | 6036 | 305.15 | 5.17 |

| OG | 6043 | 314.04 | 5.17 |

| OT | 6056 | 314.41 | 5.15 |

| NT | 6030 | 321.91 | 5.14 |

| DT | 6031 | 305.14 | 5.03 |

| DE | 6040 | 270.80 | 4.78 |

| OLB | 6027 | 245.27 | 4.66 |

| MLB | 6012 | 234.87 | 4.67 |

| ILB | 6014 | 233.76 | 4.61 |

| OCB | 6001 | 194.27 | 4.45 |

| NCB | 5110 | 194.47 | 4.49 |

| SS | 6001 | 204.01 | 4.52 |

| FS | 6001 | 201.98 | 4.53 |

| K | 5117 | 195.09 | 4.92 |

| P | 6017 | 209.84 | 4.86 |

| LS | 6023 | 240.37 | N/A |

Bucko's Lesson: Find a Philosophy

Bucko, who played guard and tackle for the Philadelphia Eagles, was a tough Irishman from Philadelphia. He had enormous hands and was a very thick, wide-body kind of guy with a big appetite. He was well over 300 pounds when I met him. I don't know why he liked me, but he just did, and he went out of his way to teach me and help me and give me projects and tests. I would submit them to him, and he would giggle and say, "Red check! You have it wrong here."

One of the first lessons I learned from Bucko was when he got as close to my face as he could and said, "Young man, you have to learn specifically the people who are doing these jobs." Those words stayed with me my entire career. Then, he gave me an assignment. He said, "I want you to tell me the average height, weight and speed for every defensive lineman, every linebacker and every secondary player in the NFL." I had to do it by height to the eighth of an inch, weight to the exact pound and speed to the one-hundredth of a second.

When I finished accumulating that and I averaged it up, these criteria became what we used for the average player at those positions in the NFL. It wasn't the top 10 percent or the bottom 10 percent. It was the average, and it was constantly referred to by Bucko Kilroy and Mike Holovak as the prototype.

When someone brought you a player that didn't meet the prototypical structure, he was an exception. Generally speaking, the prototype height, weight and speeds were adhered to as strongly as possible. Tom Landry told me one time, "Bill, if you start drafting exceptions, pretty soon you're going to have a team full of exceptions."

When you walked on the field to play his Dallas Cowboys and you looked at their defensive linemen, you knew they were going to be tall, rangy players: Too Tall Jones, Harvey Martin, Randy White. You could look at their defensive linemen and you could see what they were looking for. If you looked at their linebackers, they were the more medium-sized, quick, speedy types.

If you looked at the Pittsburgh Steelers and their defensive line in the '70s, you saw Joe Greene and Fats (Ernie) Holmes on the inside and Dwight White and L.C. Greenwood on the outside.

If you looked at the Los Angeles Rams' Fearsome Foursome, you saw Merlin Olsen and Roosevelt Grier on the inside and Deacon Jones and Lamar Lundy on the outside.

And if you looked at the Minnesota Vikings of Jim Marshall, Carl Eller and Doug Sutherland, you began to see the philosophy of personnel at those positions they used.

The people — and former Raiders' owner Al Davis was among them — who told me if you don't have your philosophy on personnel and you don't have your prototypical values in place on personnel, pretty soon, and these were their exact words, "Your team looks like a dog pound. One of these … one of those … big ones … little ones … ones that bite … ones that don't."

Now, in addition to the positional skills, there were three critical factors for each position within this system. I'm not going to go through every position, but, for example, the critical factors for wide receiver were hands, quickness and speed. There's never been a good receiver that couldn't catch. You somehow have to create separation from the defender, and quickness and speed are vehicles to do that. A receiver needs at least one of those traits.

For offensive linemen, it's size, strength and quickness. If they're not big or strong enough, they're going to get overpowered in the league. If they don't have the quickness to get in a position to block someone, they're not going to be effective.

In the history of football, the one position that doesn't have a prototype is running back because it has always been a production position. If they gain yards in high school and they gain yards in college, there's a pretty good chance they'll gain yards in the pros. They come in all shapes and sizes. When I first started in this game, fullbacks were the primary ball carriers. Jim Brown, Jim Taylor, Rick Casares and Cookie Gilchrist were bigger guys who got most of the carries.

Then, with the advent of the I-formation in the '70s and as it became prominent in college football with John McKay, the Southern Cal coach, the tailbacks became the primary ball carriers. O.J. Simpson, Marcus Allen, Eric Dickerson and guys of that ilk became the focal point of the running game, and the fullback became a secondary position. As we evolved with the spread offenses, different kinds of backs came into play, like Emmitt Smith, Thurman Thomas, Walter Payton and Barry Sanders.

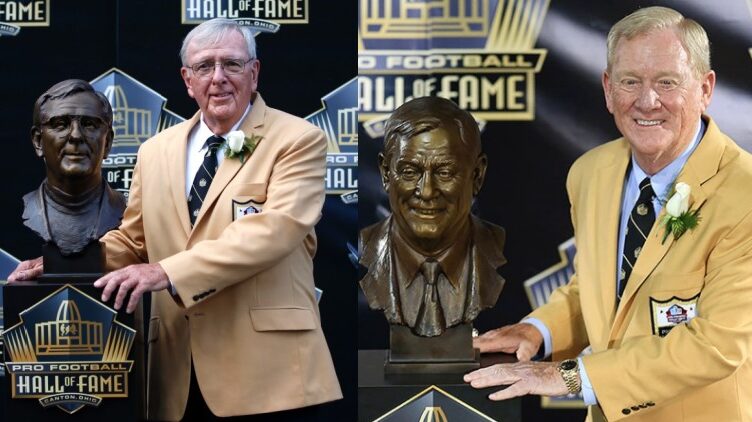

Eventually, I compared the Kilroy-Holovak scouting system to other philosophies I saw. I had some close friends in the business, such as Ron Wolf, former general manager of both the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the Green Bay Packers. His philosophy on personnel was different from mine, but he did have a philosophy, and I learned to respect that. The same was true with Bill Polian, former general manager of the Buffalo Bills, Carolina Panthers and Indianapolis Colts. With the Colts, he was selecting players for the Monte Kiffin/Tony Dungy defensive style that was completely different than what I was exposed to, but it was a philosophy, and they had a vision for personnel for it, and I learned to respect that, as well.

We evaluated the players in three specific areas. One was their personal character. What kind of guy is this? Second was the medical aspect, his injury background and general physical stature and well-being. Third were his positional skills.

Fortunately, when I went from the Patriots to the New York Giants, New England people were in the organization – Ray Perkins and Tom Boisture – and we had the same system. So, for my first 14-15 years in the league, we had the same scouting system. Then, coincidentally, when I left the Giants, I went back to the Patriots and that system was still in place.

Now, if there was someone who didn't fit that prototype, my friend Ron Wolf used to have an expression, and I used to use it quite a bit myself: "He'd better walk on water." In other words, there are certain players that are exceptions but who have exceptional skills.

But if you have too many exceptions, you'll have a team full of them … and you've got yourself a dog pound.

As told to Vic Carucci